You’ve likely heard the term ChatGPT by now. Since its launch, this past November 30th, much has been said and written about ChatGPT and its implications on the way we live, work and learn… Sometimes even by the Generative Artificial Intelligence chatbot itself.

Within five days of its launch, more than one million people had signed up to test ChatGPT, described by one New York Times article as a “highly-capable linguistic superbrain” – a head-spinning “mix of software and sorcery.”

Coming from a digital media background, and interest in the way emerging technologies apply to teaching and learning as EdTech, I was curious what the implications were of ChatGPT on education in the not too distant future – neigh…now. (Because these impacts are coming whether or not we are ready for them and have already started to massively shift what’s taking place in classrooms, at homes, and on campuses in Canada and abroad.)

What We Know About ChatGPT

ChatGPT, which stands for Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer, is based on pre-existing Large Language Model technology called GPT3 that essentially provides exceptionally-humanlike, cogent and original text responses based on what prompts you give it. But while this sounds simple, what the tool can do is much more complex than that; It can write academic essays, summaries, poems, raps, memes, and jokes (that are actually funny). It can answer trivia, translate languages, produce course syllabuses, generate original recipes (with moderate success), spit out functional if imperfect computer code or drive interactive text-adventure games, mimic pop psychologists and celebrities, produce plausible cover letters and government bills, provide inspiration to creatives, and much more, giving even its makers pause. With ChatGPT, the more specific and detailed the prompts, the more fleshed out and human-like the results.

Some even say that this invention will render search engines like Google obsolete, and put many out of a job (some say even teachers), across various creative fields – challenging our perception of just how replaceable by robots we may ultimately become.

ChatGPT comes by way of the world’s leading artificial intelligence lab, San Francisco-based OpenAI, and is partly funded by Microsoft, as well as Twitter and TESLA CEO Elon Musk. It is a neural network – a mathematical model loosely based on the human brain that scans vast amounts of digital data and recognizes patterns in that data, allowing it to learn to recognize what it’s looking at (say a cat), as well as to anticipate what comes next in a sequence of text.

It essentially makes very good probabilistic guesses about how to splice together different bits of text in a way that is nuanced and makes sense. It has learned to do this by analyzing billions of examples across the Internet, including Wikipedia articles and books. Interestingly, ChatGPT won’t give you the same results every time, making each work original and difficult to trace. Depending on how you word your prompt, you’ll likely get a unique writeup, even if the context remains the same. And amazingly, it does this in seconds and at speeds no humans can compete with.

We’re already using some of this tech in facial recognition technology and spoken commands you give Google, Siri or Alexa. And OpenAI is also behind DALL-E 2 — an image-generating application that creates completely original work based on what you tell it you want to see (not without its own controversy); it builds these images with bits and pieces created elsewhere (and by someone else) on the web and raising questions about copyright and just what constitutes original work (can we say the same of remixed music?).

OpenAI’s latest model, GPT-3, scanned more digital data than its predecessors (it trained on 540 billion words to be exact), and its programmers are working to resolve issues with problematic language prior models generated (more on this in a bit).

Not only did ChatGPT disrupt what many of us thought currently possible for an AI-fuelled chatbot to accomplish, but it’s also only the beginning, as the tech continues to evolve and learn (cue semi-jokes about HAL3000 and Isaac Asimov-esque plot twists).

All this raises questions about whether we are at that inflection point of singularity – an irreversible future history in which the sentient robots we created cease control and reign supreme. To be clear, it’s hard to make a case for this at present. But still, we are nearing the text equivalent of what roboticist Masahiro Mori termed the “Uncanny Valley” in 1970 (the idea that there is a point past which a robot’s physical likeness to a human becomes deeply unnerving).

How It’s Revolutionizing Teaching, Learning, and… Well… Everything

Now let’s talk about how ChatGPT can impact teaching and learning. Paradigm shifts in teaching and learning aren’t unusual. Just think of the shortcuts calculators, grammar and spell-checkers, reading guides such as Cliff Notes and even the World Wide Web introduced. Students regularly carry the Internet in their pocket, and access to resources has never been easier for much larger segments of society (though still, unequally and incompletely).

Its applications to teaching range anywhere from doing academic essays, summaries and assignments for students, to providing thought-starters, to even helping teachers and professors create recommendation letters, syllabuses, assignments, assignment rubrics and even grading those assignments according to those rubrics, all in startlingly human-like ways. There is even talk of personalized teachers or virtual tutors for everyone with access to the Internet. Still, some school boards are already moving to ban ChatGPT on school property and computers.

ChatGPT: Teaching and Learning Opportunities

Without hesitation, ChatGPT is impressively good at what it does and the speed at which it does it. Like YouTube or the Khan Academy or similar free resources, it can serve up information at the desired level of simplicity or complexity, meeting prospective students where they are in their learning journey. This is a good thing.

Also, some enterprising folks are already working to implement similar technologies in competitive test-prep markets, such as those found in Japan, Korea and Colombia (one such company is Riid). The aim here is to track student performance, even predict future scores, and provide personalized feedback at faster speeds than mock tests. These technologies are also now making their way to the United States to help students prep for their SATs and ACT college entrance exams.

ChatGPT: The Known Issues

While nevertheless impressive, ChatGPT is not flawless (it sometimes gets code wrong and even fails at relatively simple math problems). It also isn’t consistent.

As mentioned, previous versions of ChatGPT were also particularly plagued by problematic, biased and hateful language that is only all too readily available on the Internet. It’s essentially only as good as its base material, and we don’t need to look very wide or very far to spot inaccurate, or outright biased information there.

Unlike Google and other search engines, its last full data scan was in 2021, so the information is also pretty dated in some respects. Anything that took place after that last scan isn’t part of its parameters or included in its range of answers. Thankfully, this is made clear on the free trial page to level-set.

ChatGPT is also Switzerland on many issues, so you won’t find strong opinions unless you sneakily circumvent its guardrails. This is by design, to avoid offensive language (as mentioned) – issues with the application raised in earlier versions. Instead, what you’ll get is an overview of what beliefs others may hold.

Still, one of the earliest flags raised is that ChatGPT would lead to fraudulent academic essay writing for students looking for low-lift shortcuts, impacting their motivation to learn. One article even declared the end of high school English, asking whether essay-writing is still quintessentially a marker of understanding and intellect. The possible growing reliance on such applications has clear implications on students’ growth and learning how to research for themselves and to clearly communicate their thoughts and feelings (the process of writing itself can be self-revelatory and can help someone comb through their thinking). ChatGPT can also edit and finetune essays too (currently though, text length remains at 4,000, but it wouldn’t be impossible to work around this limit with enough imagination.

However, ChatGPT is hardly the first shortcut for enterprising students, motivated to bypass schoolwork. (The same article above notes the existence of the Photomath app, which has been around since 2014, and which enables students to get solutions to math problems, and of paid essay-writing services). But ChatGPT changes the breadth and ease of access to such shortcuts, lowering the barrier to entry and forcing educators to rush to modify the way they teach.

One concern is that students would misrepresent their work, and where software such as Turnitin can help detect plagiarism by identifying text found elsewhere, this isn’t possible with ChatGPT because it spits out entirely original works, and no easily-identifiable reference points exist. (According to TechCrunch, OpenAI is working to integrate watermark-like identifiers on generated responses to help clarify its authorship.)

Otherwise, the burden falls to already-busy teachers to figure out whether their student or a chatbot completed the assignment. ChatGPT told an Associated Press reporter that indications it may be the author based on the following signs:

- Absence of personal experiences or emotions

- Inconsistency in writing style (such that may come from spliced together text from a variety of sources and authors)

- The presence of repetitive phrases or filler words

ChatGPT: Mirroring Blind Spots

While I’ve already noted that prior versions of ChatGPT had blatant bias and offensive language, these considerations go further than simply text on a screen. Here is what I mean: if the source material for ChatGPT is largely, say, English-speaking or generated in North America, than the resulting answers will be skewed towards dominant ideas and language to that source material, at the exclusion of others.

My Master in Teaching research focused on gaming in education. In much the same way that the framework of a game can unintentionally steer gameplay by virtue of its guardrails, so too can code, and the applications that code drives. And bias in coding is nothing new – this is why there are calls to diversify computer science, to help mitigate even unintentional blindspots (Black Girls Code is one org working to change this).

ChatGPT’s guardrails (its known parameters) are only as inclusive or as exclusive as the source material it draws its information from, and we know the digital landscape is littered with questionable content, at best. Still, debate is emerging about whether there should be a language filter added to ChatGPT and exactly what constitutes AI censorship (currently, the app screens for racist, sexist and other offensive language).

More still, users are also sharing plenty on TikTok and elsewhere about how they are managing to circumvent ChatGPT’s guardrails, so even these filters aren’t perfect and access to illicit instructions remains possible.

Another issue with ChatGPT is that even as we know it isn’t always accurate, it nevertheless gives answers with the kind of definitive confidence that can further muddy fact from fiction (what scientists call hallucination). Taking such text at face value would only spread misinformation.

In one eerie example, data scientist Teresa Kubacka asked ChatGPT to explain “cycloidal inverted electromagnon” (which doesn’t exist), and it in turn spat back out an eerily plausible-sounding answer, backed by non-existent expert sources. These results were even convincing to a trained data scientist, never mind to those with less life and educational experience (or bandwidth) to drill down whether such answers were legitimate.

On a small scale, this is worrisome for individual students and classes, but what might happen if such applications spread disinformation at rates we simply can’t compete with, essentially flooding the digital landscape with convincing but inaccurate content? And how can we prevent it?

Even Sam Altman, co-founder of OpenAI, recognizes the technology has its flaws: “ChatGPT is incredibly limited, but good enough at some things to create a misleading impression of greatness,” Altman tweeted. “It’s a mistake to be relying on it for anything important right now. it’s a preview of progress; we have lots of work to do on robustness and truthfulness.”

Called a “multiplier of ability,” ChatGPT may further exacerbate the unequal distribution of teaching and learning resources, and thus amplify the divide between the haves and the have-nots.

Beyond ChatGPT’s Limitations

Even with its limitations and more nefarious possibilities, ChatGPT underscores even greater need for digital literacy among students (and the rest of us, really).

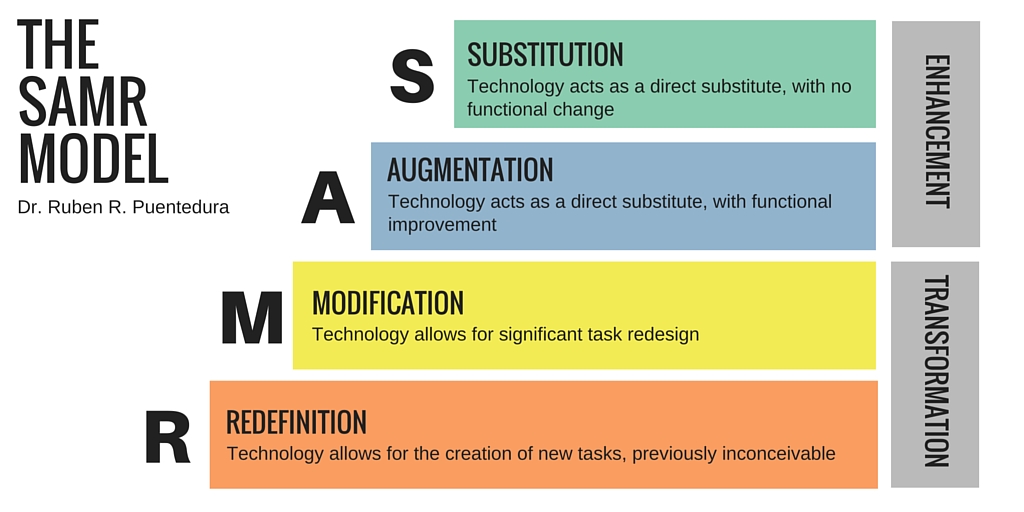

The SAMR model is a helpful framework that can help educators understand and categorize emerging EdTech and its value to the classroom. It essentially breaks down the function of the tech as either Substituting, Augmenting, Modifying or Redefining the way students work and think and teachers teach. The most valuable tech is said to reach this final level of Redefinition, and it’s hard to argue against ChatGPT doing just that.

Though nothing can truly replace the genuine in-person connections teachers form with their students, the idea of a digital teaching assistant to busy, in-person teachers who teach large classes with varying student needs does sound appealing to many. So too does receiving data-driven, real-time feedback on student performance so teachers may better understand how to focus their instruction to help fill learning gaps, where teacher intuition isn’t enough.

Other ways teachers may bring in ChatGPT in a thoughtful way include the ideas below:

- Challenge students to guess what was AI-generated versus what a student wrote (to test yourself, see this New York Times experiment)

- Go on a fact-checking scavenger hunt and to check an AI-generated essay or to verify sources (and weed out poor ones) and share findings with the rest of the class

- Edit the essays, adding depth and consistency

- Challenge students to write out an essay or a story based on what ChatGPT brainstorms

- Organize debate around the value and drawbacks of turning to chatbots to write for us, en masse (What do we lose? What do we gain?)

- Organize debate on what constitutes AI censorship and whether we should employ it

In these examples, you’re encouraging students to see ChatGPT as a tool, rather than a shortcut or an answer.

Final Thoughts

Technological disruption isn’t smooth by definition, so no wonder there’s much to grapple with when it comes to ChatGPT. And we’ve only nicked at the surface of its huge potential (the next version of the company’s Large Language Model – GPT4 – is set to be released sometime this year).

As it improves through an iterative deep learning process of extreme trial and error, we can expect that ChatGPT and other similar applications will only get better at mimicking human responses, whether through text, verbally or even visually, generating entirely original (and some completely made up) responses.

What is indisputable is that as we get a better grasp of its potential, ChatGPT also offers new opportunities to emphasize and teach critical thinking (one of the 21st century learning competencies I explored in an earlier post). And because ChatGPT is unlikely to go away or to be disarmed completely, it’s perhaps best to instead learn how to work with it rather than against it, and to similarly help students do the same; when viewed more as a tool than as the answer, ChatGPT holds enormous promise. Because, as with all tools, whether the outcome is positive or negative depends largely on the tool’s wielder.